The Middle English group at Stavanger has been active since 2006. We study late medieval texts written wholly or partly in English, especially through sociolinguistic, pragmatic and philological approaches.

About the Middle English group

The Middle English group at Stavanger has been active since 2006. We study late medieval texts written wholly or partly in English, especially through sociolinguistic, pragmatic and philological approaches. We call our work the Middle English Scribal Texts Programme (MEST). The crucial term is ‘scribal text’: we are interested in the actual physical texts that survive, who wrote them, where and when and for what purpose.

Why Middle English?

First of all, because it allows us to study large quantities of historical English texts that were produced in a multilingual context and in a manuscript culture, with all the fluidity and variability of handwritten text production. Secondly, because of the extreme linguistic variation in this period, when there was not yet an established standard model for writing, and linguistic habits could vary tremendously. We can address this variation in relation to factors such as geography, genre, function, audience, gender, education, institutions and sponsorship.

This makes Middle English an exceptionally interesting area of study, not least from the point of view of the changes to technology and literacy practices in our own time, which may cause us to question things that were taken for granted in a print culture: the identity of a text, the necessity of a standard language, the role of education.

This makes Middle English an exceptionally interesting area of study, not least from the point of view of the changes to technology and literacy practices in our own time, which may cause us to question things that were taken for granted in a print culture: the identity of a text, the necessity of a standard language, the role of education.

What do we do?

A large part of our work so far has been to produce text corpora – digital collections of texts transcribed directly from images of the manuscripts.

A large part of our work so far has been to produce text corpora – digital collections of texts transcribed directly from images of the manuscripts. We produce them in formats that can be either read or searched, and which have a great potential as research materials. We are making available texts that otherwise have to be studied in archives or libraries, and providing ways of analysing the variation found in them in relation to a large number of variables.

In 2008, we launched the first version of the Middle English Grammar Corpus (MEG-C), based on samples of texts of various genres (from recipe books to saints’ lives), dated to ca 1325-1500. The MEG-C project was funded by the Norwegian Research Council, and the main compilers of the corpus were Merja Stenroos, Martti Mäkinen, Jeremy Smith and Simon Horobin. The latest version, MEG-C 2011.1, contains 410 texts and over 800,000 words.

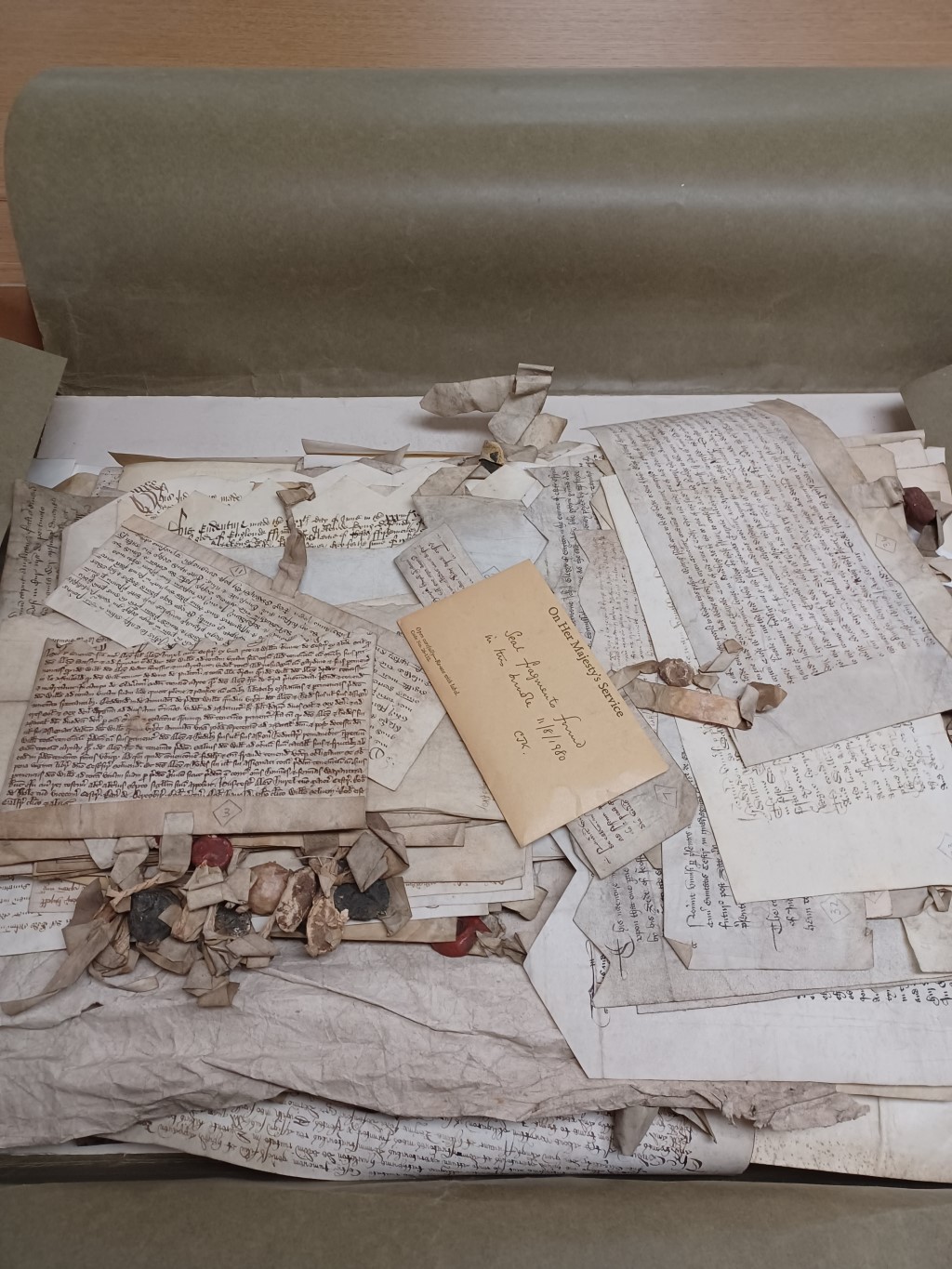

In 2012-16 we carried out another five-year project, Language and Geography of Middle English Documentary Texts, funded jointly by the Norwegian Research Council and the University of Stavanger. This project focussed on documentary texts: legal, administrative and business documents and letters that are dated and connected to specific places. Relating language to real people and places, rather than reconstructing expected dialect patterns, has been a new approach in the field, and one that we have developed during our project work.

In 2017, we completed the first version of A Corpus of Middle English Local Documents (MELD), with transcriptions of ca. 2,000 local administrative texts and letters from the period 1399-1525 and from all over England. The documents were identified and photographed during visits to more than 70 archives, libraries and castles. Part of the MELD corpus is already available online (last updated in 2020). After a few years’ pause, we are now working on expanding and developing the corpus as part of the LiTra project.

Some of the research results of the Documentary Texts project are presented in a book volume, Records of real people: linguistic variation in Middle English local documents (ed. Merja Stenroos and Kjetil V. Thengs), published by John Benjamins in the series Studies in Historical Sociolinguistics. Others have appeared in published articles and chapters, and include pragmatic studies of medieval letters, studies of punctuation and handwriting, of sounds and spellings, vocabulary and multilingual practices.

There have also been several Masters and PhD projects connected to the projects.

The LiTra Project

From January 2025, we have begun work on a new project, funded by the European Research Council (ERC): Linguistic Traces: low-frequency forms as evidence of language and population history (LiTra).

The LiTra project brings together the experience we have built up in working with late medieval documents with the considerable technological advances of recent years that will enable us to study the materials in a much more efficient way. In the LiTra project, we will expand and develop the MELD corpus, and use it together with other source materials to ask new questions: in particular, what can linguistic variation at a very small scale tell us about the past?